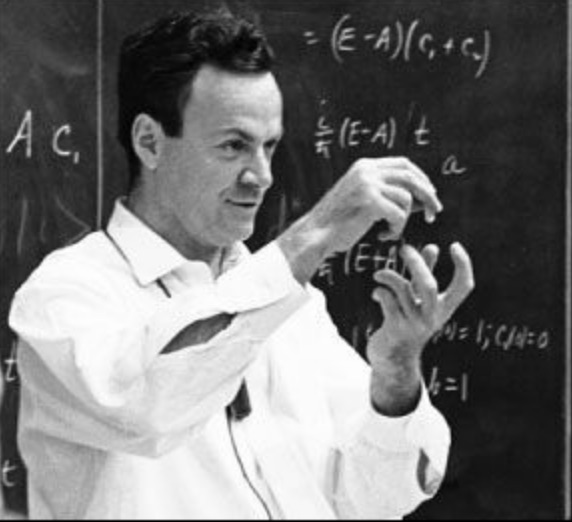

Richard Feynman (1918-1988) was one of the most highly regarded physicists of the 20th Century. He had an uncanny knack for getting to the heart of a problem with simple language and insights. His work had an impact not only in fundamental physics but he posed challenges to explore new areas such as nanotechnology or quantum computing, and also, perhaps surprisingly, science and religion.

Feynman explored the relation between science and religion in a public lecture given in 1963 at the University of Washington in Seattle. The lecture was published posthumously in 1998 in a little book called The Meaning of It All.1 Feynman made several valuable points in the lecture. He also issued a pointed challenge that calls for our attention.

First of all, Feynman recognized that science in and of itself does not answer all important questions we pose to the world. It neither shows us the meaning of our existence nor how we are to behave. Such questions, which are so important for guiding how we live our everyday lives, lie beyond the scope of the scientific method. Feynman says:

Scientists take all those things that can be analyzed by observations, and thus the things called science are found out. But there are some things left out, for which the method does not work. This does not mean that those things are not important. They are, in fact, in many ways the most important. In any decision for action, when you have to make up your mind what to do, there is always a “should” involved, and this can not be worked out from “if I do this, what will happen?” alone. (pp. 16-17)

Why can’t we conquer ourselves? Because we find that even the greatest forces and abilities don’t seem to carry with them any clear instructions on how to use them. … The sciences do not directly teach good and bad. (p. 32)

These points are uncontroversial ones with which most scientists would agree. To give but one example, science can tell us about mass-energy conversion and how to build a nuclear weapon. But science can not tell us whether we should do so, or if so, how it should be used. To decide what is ethical comes from sources of wisdom that lie beyond science per se.

Feynman was not a religious believer but recognized that science does not settle the question of the “mystery of existence:”2

What then is the meaning of it all? What can we say to dispel the mystery of existence? If we take everything into account, not only what the ancients knew, but also all those things we have found out up to today that they didn’t know, then I think that we must frankly admit that we do not know. (p. 33)

Yet Feynman was well aware of the importance of the religious heritage of our civilization:

Western civilization, it seems to me, stands by two great heritages. One is the scientific spirit of adventure—the adventure into the unknown, an unknown that must be recognized as unknown in order to be explored, the demand that the unanswerable mysteries of the universe remain unanswered, the attitude that all is uncertain. To summarize it: humility of the intellect.

The other great heritage is Christian ethics—the basis of action on love, the brotherhood of all men, the value of the individual, the humility of the spirit. These two heritages are logically, thoroughly consistent. But logic is not all. One needs to follow one’s heart to follow an idea. … Is the modern church a place to give comfort to a man who doubts God? …How can we draw inspiration to support these two pillars of Western civilization so that they may stand together in full vigor, mutually unafraid? That I don’t know. (pp. 47-48)

Feynman was being honest: he clearly acknowledged that he did not know how to put science and religion together: more specifically how to put the scientific spirit of adventure together with a motivated Christian ethic based on love. But his challenge to do so–I call it the Feynman Challenge–remains a crucial one to address: “How can we draw inspiration to support these two pillars of Western civilization so that they may stand together in full vigor, mutually unafraid?”

It is my firm conviction that Feynman’s challenge can be met. A fruitful response from the Christian side would need to call upon the deepest resources of “mere Christianity” to frame an honest response that coheres with all we actually know about reality from the various sciences, as well as respecting all that we do not know. It will require the humility of intellect and spirit that Feynman so admired. Furthermore, it will need to inspire both our hearts and minds.

If one wishes to address “the meaning of it all,” one must be mindful of the philosophical quest of the human mind that has spanned millennia of diverse human civilizations. Any specifically Christian response needs to be Christ-centered, that is, informed by the logic of the Word-made-flesh seen in Jesus of Nazareth and, consequently, informed by the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures.3 Such a path of “faith seeking understanding”4 upholds respect for the “mystery of our existence,” as Feynman so aptly expressed it. It must also seek to be Reality-centered, accounting for all we actually know about the world from the sciences and human experience. Such logic holds together knowing (science) and unknowing (mystery) in a dynamic tension that requires humility and motivates an ethic of love centered on the character of God. It opens us to see goodness, beauty, and truth as real aspects of Reality, not just productions of our “subjective” imaginations.5 Such a path is open to all. Whatever inspiration it gives must come from its own attractive power, never from coercion.

Let me call your attention to the sermon, “Truth, Mystery, and the Limits of Human Understanding,” by Alister McGrath, given at the University Church in Oxford, England (posted Nov. 11, 2016). McGrath is the Andreas Idreos Professor of Science and Religion at Oxford University. He has written extensively on topics relating to science and Christianity. His thinking is broadly consonant with my experience as a scientist and believer. It moves in the right direction to take up Feynman’s challenge.

Postscript: My original 2020 post has been updated to include newer material.

________________________________

Notes

1. Richard Feynman, The Meaning of It All (Allen Lane, The Penguin Press, London, 1998); the page numbers given for the quotes are taken from this edition. The book was published in the USA in the same year by Addison Wesley under the title, The Meaning of It All: Thoughts of a Citizen Scientist, and several other editions are currently available.

2. I will differ from Feynman on how much we can “know” about the “mystery of our existence.” The deepest mystery of our existence is the mystery of being, that there is something rather than nothing. A second related mystery is the intelligibility of the world to human beings such that we can have knowledge and “do science.” One cannot address these twin mysteries without also doing metaphysics, that is, looking “beyond physics” to ask why physics is possible in the first place. A lot is going on with that little word “to be.” To Thomas Aquinas “to be” (esse) was the “actuality of all acts, the perfection of all perfections” (in De Potentia Dei, Question 7, Answer 2, Reply 9). See this essay of mine that looks at Aquinas’s take on being and the remarkable reach of the human mind to comprehend the universe. I have a much more detailed exposition on these matters in two presentations I made in 2022.

3. The ancient way of reading the Scriptures was not merely literal. Rather it sought a deeper meaning that is “truer than literal.” To the Christian philosophical mind, the union of the human and divine in the one person, Jesus Christ, provides the fundamental analogy by which to understand the whole of Reality, the intersection of the immanent and transcendent dimensions of time and eternity. See my essay Time and Eternity: A Christological Perspective. which looks at time from the cosmological scale to that of atomic phenomena. As Saint Paul wrote to the Christian community in Colossae concerning Christ, “He is before all things, and in Him all things hold together” (Colossians 1:17 NASB). The opening to John’s Gospel introduces Jesus with these striking and precisely chosen words: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. He was in the beginning with God. All things came into being through Him, and apart from Him nothing came into being that has come into being. … And the Word became flesh, and dwelt among us …” (John 1:1-3, 14 NASB).

4. The majority view within the historical Christian tradition has been that faith and reason work together in mutual support. Augustine of Hippo (354-430) taught “nisi credideritis, non intelligitis:” “unless you believe, you will not understand.” Augustine and Anselm of Canterbury (1033-1109) are associated with the phrase “fides quaerens intellectum” meaning “faith seeking understanding.” One must first place one’s faith in something trustworthy in Reality in order to start any significant endeavor. This necessity of such trust was explained by Aristotle in Posterior Analytics (see, for example, Book II, Part 19) and is used by any modern scientist, whether it is recognized or not. The great physicist Max Planck said: “Anybody who has been seriously engaged in scientific work of any kind realizes that over the entrance to the gates of the temple of science are written the words: Ye must have faith. It is a quality which the scientist cannot dispense with.” (in Planck’s 1932 book, Where is Science Going? The Universe in the Light of Modern Physics). In both science and theology, it is Reality itself that holds the answers we are seeking. We must be respectful of how what is most real shows itself to us, given all that we know about the world and ourselves.

5. I give a fuller exposition of this in the links given in Footnote 2 above.

I like the two strands of West Civ Feynman identifies, but to hold together they must have a third. There is an ontology – deep reality – that holds them together. You suggest this in your footnotes. I hope you finally write your book about it! Pax

LikeLike

Thanks! It is precisely that ontology I intend to write about. That is the missing piece in Feynman’s analysis. Perhaps this site can be the start of a book.

LikeLiked by 1 person