by Paul S. Julienne

This is a contributed talk I gave at the 48th annual conference of the American Maritain Association, April 4, 2025, Naples, Florida. The conference theme was “the range of reason.” The version here has additional ending material, “Towards a better science,” plus extensive footnotes that were not possible to include within the time limit of the original talk, which only included the sections Introduction, Science, Philosophy, Theology, and the quotes from Torrance, Schmemman, and De Koninck at the end. A PDF file with slightly longer and fuller end material than here is available at this Dropbox link (19 single-spaced pages, 10,200 words, 54 minutes reading time).

Introduction

On January 24, 1949, Jacques Maritain gave the Suarez lecture at Fordham University that came to be the first chapter in his book, The Range of Reason.[1] In his opening paragraph, he says that: “Nothing is more important than the events which occur within that invisible universe which is the mind of man. And the light of that universe is knowledge.” In 1949, Maritain was acutely aware of the 20th-century civilizational devastations wrought by disorders of knowledge and desire in that invisible universe brought about at least in part by nominalistic, empiricist, and positivistic ways of seeing the world that had come to define what it means to be “scientific.” The Dominican moral theologian Servais Pinckaers, in a striking turn of phrase, called nominalism “the first atomic explosion of the modern era.”[2] Indeed, explosions tear things apart, and Pinckaers lists some of the fragmentations that flow from a nominalistic understanding of being and will: “freedom was separated from nature, law, and grace; moral doctrine from mysticism; reason from faith; the individual from society.” Such separations are all too familiar in our modern world.

Early modern scientists used William of Ockham’s very sharp philosophical razor to shave off Aristotelian natures and formal and final causes as useful principles for the scientific knowledge of the world. Ultimately, the practice of modern science came to be blind to the transcendental unity of the true and the good to which Thomas Aquinas had borne witness in the opening article of his treatise De Veritate. If the true and the good are thus separated, it is not surprising that virtually all scientists now say that empirical scientific knowledge about how the world works, that is, the true, does not in itself tell us which use of that knowledge is right or wrong, that is, how it should be properly oriented to the good. This is not entirely wrong, since Maritain himself knew that there were degrees of knowledge, of which the “empiriological” aspect was but one. Yet, as Michael Hanby has argued,[3] technology has come to be the defining ontology of modernity, by which we see knowledge as power, power to control and transform the world according to our human wills, all too often unconstrained by any transcending order of the good. While technology can and has served many good ends to the good of humanity, it can also serve the disordered ends of disordered human loves and desires unless these are ordered to a properly true human good. Without a transcending order of the whole by which it is meaningful that things have natures, we will no longer know what a thing is (its formality), nor will we know what it is good for (its finality). To take but one example, if we do not know what true human intelligence is, how will we ever know what the term “artificial intelligence” might mean, or whether or under what conditions the use of such technology might be good or bad?

Maritain concludes his opening paragraph by saying, “One of the conditions necessary for the construction of a world more worthy of man and the advent of a new civilization is a return to the genuine sources of knowledge, an understanding of what knowledge is, its value, its degrees, and how it can create the inner unity of the human being.” Science in its modern sense concerns a particular kind of knowledge and how to obtain it. This paper takes up Maritain’s challenge to understand the full scope of human knowledge and reason. It begins by considering some of the distinguishing features of modern science. Then, following a principle of David C. Schindler that “human reason is essentially catholic, kath’ holon, ‘according to the whole,”[4] it draws upon the philosophical wisdom of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas to situate science within a greater whole. Along the way, the paper commends the thesis in Andrew Younan’s recent book, Matter and Mathematics [5], that an Aristotelian essentialist account of the laws of physics is a key to returning nature, form, and finality as real principles of the intelligibility of the world. But Aristotle’s insights need to be deepened by Thomas Aquinas’s philosophical vision of all being kath’ holon, where we do not lose sight of the unbounded reality of goodness, truth, beauty, and love at the heart of the world, grounded in Subsistent Being Itself, which St. Thomas knew to be most powerfully expressed in the mystery of Triune Love. To St. Thomas, a mystery was not a puzzle or something dark and merely unknown but something made manifest, revealed, with a depth of inexhaustible intelligible light that exceeds our ability to comprehend fully.[6]

Maritain’s classic 1932 book on knowledge[7] has the French title “Distinguer pour unir, ou les degres du savoir.” While Maritain’s principle, “distinguish in order to unify,” is undoubtedly significant, physicist David Bohm makes a case for the reverse: “unity is prior to distinctions.” Bohm takes his cue from the necessity to account for strange and counterintuitive quantum phenomena which must be seen kath’ holon, according to an implicate order of the whole.[8] Apparently distinct and multiple atomic events only make sense in the light of a greater whole in which they are enfolded. Both Bohm and Maritain are each right in his own way, in that unity grounds distinctions and distinctions reveal unity. Let us now take a brief look at the scope of contemporary science. Then Aristotle and St. Thomas can help us see how science can be guided by a truer and more unified logic of being than the disunity of nominalistic separation.

Science

Albert Einstein is one scientist who saw the miraculous wonder of the intelligibility of being. In a 1936 essay he said, “The eternal mystery of the world is its comprehensibility … The fact that it is comprehensible is a miracle [German: “ein Wunder“].”[9] To state the fact that the cosmos is comprehensible is to see that the human mind has the capacity to truly grasp something essential about the things in it. Maritain said, “If I … am a Thomist, it is in the last analysis because I have understood that the intellect sees, and that it is cut out to conquer being.”[10] If there is a key point you should take away from this presentation, it is that the human being truly sees being by seeing beings, and by virtue of that seeing brings being to speaking, to human articulation in intelligible words, even in the mathematical speech of the equations by which we formulate the “laws of physics.” To see being according to its mathematical aspects is good, for the Wisdom that is the source of all things not only “orders all things well” but has “arranged all things by measure and number and weight.”[11] To be a scientist is good, for it conforms to the telos of our human nature to comprehend and articulate all dimensions of that ordering. This is part of the human vocation to bear witness to the unity of our origin and our end. St. Thomas helps us see the crucial role of our active minds in rendering the world intelligible, thus enabling the procession of an intelligible word from us.[12] St. Thomas’s philosophical theology teaches us that we must, like Maritain and Einstein, see being under the aspect of intelligible mystery, incomprehensively comprehensible, neglecting neither pole of this aporia. That too is a lesson of quantum physics.

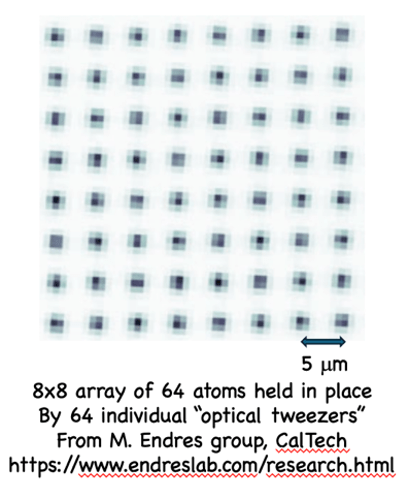

Some examples from contemporary physics illustrate the enormous range of scientific reason. First, Figure 1 indicates on a logarithmic scale of powers of 10 the scope of time that can be accessed using the best scientific instrumentation. This ranges from the cosmological scale of 14 billion years, roughly 44 thousand trillion (4×10+16) seconds, to the incredibly fast “tick rate” of the best optical atomic clocks, for example, the strontium clock that oscillates at a precisely measured rate of 429,228,004,229,874 (429 trillion) times per second.[13] The knowledge we have about stars and galaxies comes to us from the light they emit and can interpret because we now know the quantum properties of each kind of atom that give it its own quantum “fingerprint” written in the light it emits. In an example of extraordinarily short time phenomena, the response of electrons to the light striking the retinal molecules in your eye occurs on a time comparable to only one “tick” of a strontium clock (2×10-15 seconds). Thus, comprehensible processes that affect current human life on earth, from the science of vision to the evolution of life as a whole, extend across the entirety of this vast span. When shown on a logarithmic grid, the human scale of seconds, minutes, or hours stands in the middle of this scientifically accessible range of more than 30 powers of ten. The basic laws of physics allow us to give a unified account of it all, even if there are still a lot of loose ends.

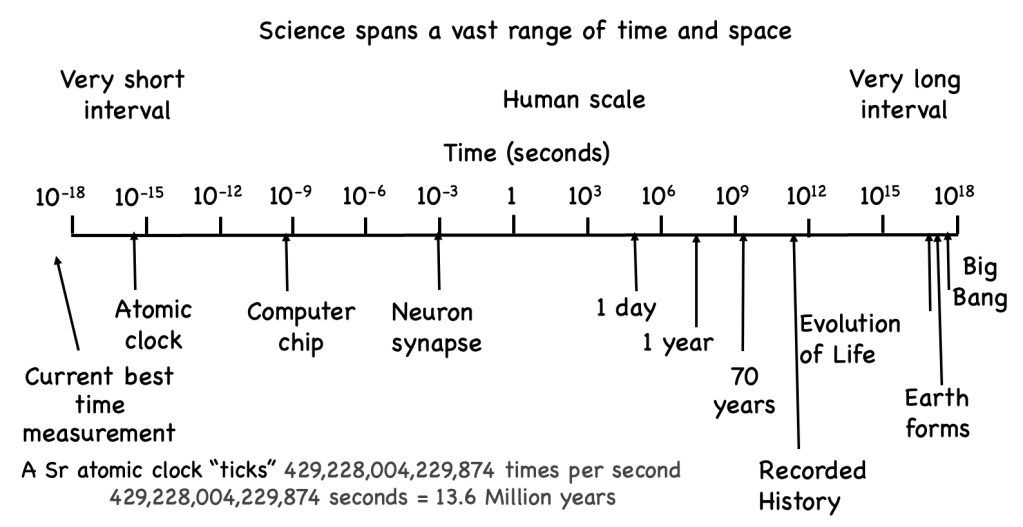

Figure 2 shows a low-resolution “atom microscope” image of 64 single strontium atoms placed in an 8 by 8 array spaced 5 micrometers apart (0.005 millimeters).[14] Scientists now routinely confine individual atoms in atom traps and place them in ordered arrays precisely where they want them[15] and image patterns of a few to many thousands of individual atoms. Many scientists around the world are trying to make a “quantum computer” or “quantum simulator” using such arrays, where each individual atom serves as a “quantum bit” that can be entangled with other quantum bits in a “quantum” way that no possible Newtonian “classical particles” could possibly do. Einstein was bothered by quantum entanglement, calling it “spooky action at a distance,”[16] but the actuality of such action has been repeatedly verified in the laboratory, and three pioneers were honored by a Physics Nobel Prize in 2022.[17]

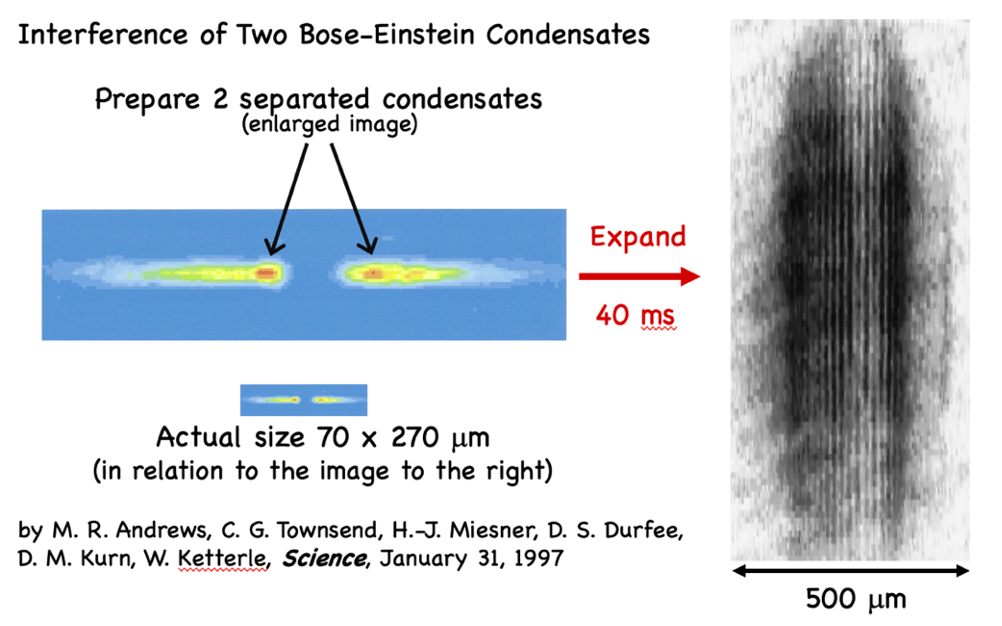

In 1997, scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) did a simple experiment that exhibited the remarkable properties of a uniquely quantum entity that Einstein predicted in 1924 based on the mathematical insights of the young Indian physicist, Satyendra Nath Bose. The first laboratory realization of a Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC) was achieved in 1995 at MIT and additionally at a joint laboratory of the University of Colorado and the National Institute of Standards and Technology. The 2001 Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to scientists at these three laboratories for this long-sought achievement.[18]

Figure 3 illustrates an experiment done in 1997 where the MIT scientists prepared two such condensates with around 30 million sodium atoms in each at a temperature just a few billionths of a degree above absolute zero held in place in a vacuum by focused laser light.[19] When the light was turned off and the atoms released so as to expand into the vacuum, an image of the much larger expanded gas after 40 milliseconds shows an “interference” pattern of atoms: there were dark stripes where there were lots of atoms, and the light stripes are where there are almost none. Physicists can precisely account for the stripes in the BEC by using relatively simple mathematics to calculate the probability of finding an atom at any given point. By contrast, a “normal” gas (not prepared as a BEC) at a slightly higher (but still very cold) temperature shows no such stripes.

What tale can one spin about a BEC? We must be careful, since Niels Bohr told us: “We must be clear that when it comes to atoms, language can be used only as in poetry.”[20] Recall that the root meaning of “poetry” is ποίησις, poiesis, that is, making or construction, something we do or make. Werner Heisenberg mirrors Bohr: “Quantum theory provides us with a striking illustration of the fact that we can fully understand the behavior of a thing [mathematically] and at the same time know that we can only speak of it with pictures and parables.”[21] David Bohm was surely also right that the secret of the atoms is held within the implicate wholeness of the quantum field that the mathematics tells us how to calculate. Thus, Bohr and Heisenberg’s “Copenhagen interpretation” counseled epistemic humility and respect for how the “quantum world” manifests itself, whereas Bohm called our attention to the necessity to see according to the whole. We must tell some tale, and a good one concerns the “quantum field” that mathematically represents the BECs: each atom within the field that describes the whole is the same and is everywhere in the BEC cloud while no atom is anywhere in particular, yet in the 1997 experiment some atoms were missing in the light stripes and others bunched up in the dark regions because of the “quantum interference” of two “coherent matter waves.” Such is the poetry by which a physicist renders the world intelligible. You can understand it too once you know what the terms defined by the mathematics mean, but the poetry never dispels the mystery. While a computer can calculate mathematical probabilities very well, perhaps one should ask if it can touch the mystery the way the human intellect can.

Philosophy

The popular science writer and quantum gravity theorist Carlo Rovelli published an article in 2018 in the journal Foundations of Physics entitled “Physics needs Philosophy, Philosophy needs Physics.”[22] Rovelli gives an appreciative nod to Aristotle in making two points: first, good theory supports and is useful in the development of practical matters, and second, one is already doing philosophy when one wishes to deny the usefulness of philosophy, as some scientists now do. D. C. Schindler makes a related point that “praxis is always and without exception rooted in and expressive of theory.” [23] Theory takes its meaning from the Greek word theoria, the act of viewing or observing, as well as the sight or spectacle seen;[24] the theoros is the one who sees. What we do in the world (praxis) depends on what we see the world to be.

Now let us turn to Aristotle to establish some basic principles. The opening line to his Metaphysics, translated by J. Sachs to be close to the literal Greek, reads: “All human beings by nature are stretched out towards knowing.”[25] There is already a world of metaphysics in this simple statement. We learn that there is a class of beings called human beings about which we can predicate “all,” and all these beings have a nature (φύσις, phusis) that gives them a desire, that is, “stretches them out,” to know, expressed here by the Greek infinitive εἰδέναι, eidenai, coming from the verb εἴδω, eido. The Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek tells us that eido and the related noun eidos both have rich semantic depth circling around the notion of seeing, perceiving, being like, knowing, or understanding. The noun eidos can variously be translated as appearance, shape, form, species, nature, or prototype. It is also one of the words Aristotle uses for “form,” which Sachs characterizes as “the invisible look of a thing seen only in speech.”[26] To Aristotle, a real existing thing, a “substance” (οὐσία, ousia), is a union of “matter” and “form,” often called a “hylomorphic” entity.[27] To Aristotle, form does not exist in some ethereal Platonic Realm of the Forms. Rather, eidos is only found in specific real corporeal things as a real internal springboard of their activity, their ἐνέργεια, energia, their most essential act translated by Sachs as “being-at-work”. Maritain gives the name “eidetic visualization” to the act by which the intellect abstracts eidos from the sense impressions we receive from things in the world.[28] Form is the principle of intelligibility. Without form, nothing ultimately “makes sense.” It is only because our minds can abstract form from the individual things in the world that we can say anything at all. It is a key to all human understanding and is at the heart of “Thomistic noetics.”[29]

The opening chapter of Aristotle’s Physics tells us the knowledge and understanding of things comes from knowing their “beginnings” (ἀρχαὶ, archai), “causes” (αἴτια, aitia), and “elements” (στοιχεῖα, stoicheia).[30] The term ἀρχή, arché (plural, ἀρχαὶ), has not only the sense of “beginning,” but also origin, source, foundation, or principle;[31] Aquinas renders it as “principle.” We thus can think of arché as having the sense of “originating source” or “principle.” The Gospel of John opens with the same term: Ἐν ἀρχῇ ἦν ὁ λόγος. The arché, the originating source of all things, is the Word, Λόγος. Logos comes from the verb λέγω, lego, that also means to collect, count or to gather, so that its meaning as “word” also bears the sense of “gathering in speech.” There is a fundamental connection between the archai of things and what we come to say about them. In human science, we get to say what things are, including their mathematical aspects. To Aristotle, substances or hylomorphic things, that is, real existent things in the world, have natures φῠ́σεως, phuseos (plural form of phusis), and natures and causes are both archai, and, like being, can be said in many ways,[32] according to Aristotle’s rich analogical understanding. To know a cause is to give an account of something according to its arché. To Aristotle, the nature of a thing is an internal arché of motion and rest,[33] the ἐνέργεια, energia from which it springs. St. Thomas puts it this way: “nature is nothing other than a principle of motion and rest in that in which it is primarily and per se and not per accidens.”[34] Natures, causes, and archai are not material things, but rather inhere in things as grounding principles of their activity so that things can be the particular things that they are and additionally be intelligible universally to perceiving minds.

The principles discussed above are at the heart of Andrew Younan’s thesis about the laws of physics. He argues against those he calls Humeans and anti-Humeans. To oversimplify a very complex matter, we might just say empiricists and Platonists, where the empiricists restrict understanding and natural “laws” to the ordering by our minds of a random world that has no room for Aristotelian natures or forms, whereas the Platonists have a ordered world with no credible way to show how “formal” mathematical equations known by our minds could possibly “govern” matter, that is, make it “do things” like an efficient cause. Younan sees the laws of nature as mathematical relations that our minds abstract from actual real things under their aspect of being quantitative due to their inherent natures. That explains the “unreasonable effectiveness of mathematics in physics.”[35] Real things have natures that make their formal mathematical aspects visible to us when we look rightly. Physical laws do not move things; rather, they reflect the intrinsic principles by which things move. Younan distinguishes four classical levels of abstraction from what he calls “individual substance in matter and motion,” namely: (1) the “particular matter” of real things, (2) the “common matter” of natural philosophy, (3) the “intelligible matter” of mathematics, and (4) the “immateriality” (no matter) of metaphysical knowing.

Maritain makes similar distinctions in his Range of Reason. He says: “It is necessary to recognize two essentially distinct ways of analyzing the world of sense-perceivable reality and of building the concepts required for this. The first way is by a non-ontological analysis, an ‘empiriological’ analysis of the real. This is the scope of scientific knowledge. The second way is by an ontological analysis of the real. This is the scope of philosophical knowledge.” Maritain’s first way recognizes the methods of ordinary empirical science, whereby science, “uses, as its own instruments, explanatory symbols which are ideal entities (entia rationis) founded on reality, above all mathematical entities built on the observations and measurements collected by the senses.” In a nutshell, the physicist’s “formal atom” or “noetic atom” described by the equations is not the same as the “existential atom” in the laboratory, yet there is a real and true correspondence between them. Articulating the nature of this correspondence is a key to having any intelligible “interpretation” of quantum mechanics. French physicist Roland Omnes, seeking like Rovelli to bring philosophy to physics, sees an unbridgeable “chasm” between the “formal” and “existential” aspects of the quantum world,[36] but to discuss his reasons for this is beyond the scope of this present discussion. Instead of “chasm,” it would be better to say “intelligible mystery,” a term more congenial to Thomistic noetics.

Maritain says that by this understanding of empiriological analysis, while “the human mind can scientifically dominate becoming and sense-perceivable phenomena, at the same time, it gives up any hope of grasping the inner being of things.” Yet is this quite right? For in the implicate wholeness of the single mind of a single human person who is a scientist and who also draws upon the Christian insights of Thomas, that person can, along with Maritain and St. Thomas, grasp “the inner being of things.” In an implicate order of being, the inner unity of the person has a priority over the noetic distinctions of the degrees of knowledge that the person makes, even if it is needful to make such distinctions. In other words, there is no reason why one, even as he does his empirical science, cannot also be a philosopher and a metaphysician; perhaps even a theologian. Science is practiced not just by instrument readers but by human beings with a capacity for theoria.

If nominalism has a key and valuable insight, it is the profound significance of what Aristotle calls the “τὅδετι“, tode ti, the “this” or “this what” that manifests itself in all of its irreducibly unique individuality. Scientists in the laboratory working with an individual atom or with an ensemble of atoms work with the specific and unique tode ti before them in the lab; the theoretical physicist works with the “formal atom” under the aspects of its universal mathematical principles. What nominalism misses is that the unbounded positivity of the specific, individual tode ti derives precisely from its formality and finality, its nature, as having been given to it from beyond. An existent hylomorphic entity like an atom in the laboratory is already and always informed by its immaterial form, the principle by which it is what it is in its unique individuality.[37] To see the irreducible wholeness of being through its irreducible particularity, we must turn to theology.

Theology

While Younan’s Aristotelian analysis seems basically correct, there remains the question of the grounding origin, the ἀρχῇ, of the natures, forms, and causes that are there to be abstracted from. There is a greater whole we must invoke if we are to see kath’ holon and thus see the world in its maximum intelligibility. St. Thomas’s philosophy in the light of Christian revelation reaches the grounding Source in the notion of creation ex nihilo that simply was not available to Aristotle. Creation ex nihilo does not give us details about topics like cosmology or biological evolution that are properly studied by empirical science. Rather it gives us guiding principles that govern the nature of being and its intelligibility. Thomist Josef Pieper tells us: “In the philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas, there is a fundamental idea by which almost all the basic concepts of his vision of the world are determined: the idea of creation, or more precisely, the notion that nothing exists which is not creatura, except the Creator Himself; and in addition, that this createdness determines entirely and all-pervasively the inner structure of the creature.”[38] Pieper also points out that “… this fact is not evident; it is scarcely ever put forward explicitly.” Yet, as Maritain and St. Thomas both knew, natures and formal and final causes can only be intelligible if they are grounded in a transcending order that is their arché, their originating ground.

Creation ex nihilo implies a radical difference between the being of the Creator Source and the being of created entities. To St. Thomas, the Being of God (Ipsum Esse Subsistens) is by essence (per essentiam) and is thus uncaused.[39] The being of creatures is by participation (per participationem) and thus caused.[40] Participation is a deep concept in Thomas’s thought pertaining to being, causation, human understanding, and law.[41] Participation means having from beyond, from outside oneself,[42] of the proper agency that each being has that is oriented to its end. Thus, there are primary and secondary causes; that is, while God has an ever-present primary role in upholding all created things in their existence and natures, all created things have their own real secondary agency so that they can carry out their proper operations. Human beings are embodied whole beings, hylomorphic entities, the subsistent form of which is called by Thomas the soul, or intellectual soul, since we are rational animals with a mind. Remember that form is an internal source of all activity of the creature in accordance with its nature.

The radical difference between God and creatures also means that finite human beings can never comprehend the essence of God. This requires us to use analogical language in speaking of God: “… things are said of God and creatures analogically, and not in a purely equivocal nor in a purely univocal sense. For we can name God only from creatures.”[43] Analogical predication has an “is” and “is not” structure, such that “between Creator and creature no similitude can be expressed without implying an even greater dissimilitude.”[44] This analogical interval between God and creatures introduces a fundamental and irreducible apophatic dimension to human knowing that is clearly explained by Josef Pieper. He explains that things have natures and can be known precisely because they are created. But while all things have a clarity and intelligibility that enables them to be known by us, they also have an unfathomable depth that exceeds our knowing: we can never know how God creatively thinks beings since we cannot know the divine essence, and we cannot see things “from the side of God,” so to speak. Since we can only see from the side of the creature, created things have a depth of intelligible light that exceeds our capacity to see. Pieper sees this knowable yet unfathomable character of creatures as an essential part of St. Thomas’s understanding of truth and being.[45] We must keep in mind this necessary analogical interval between our minds and all of Reality, even when we are doing physics. This is the basis for saying that all real being has the character of intelligible mystery. We will never be able to “interpret” quantum physics without this insight, for we name atoms and quantum fields from creatures also.

In discussing the “transcendental” properties of all being, and specifically the true as a correspondence between beings, St. Thomas quotes a most remarkable phrase from Aristotle’s De Anima: “The soul ‘in some way is all things.’”[46] This tells us the scope of human reason. Our intellectual soul has the capacity to take up within itself an unbounded range of things. And our knowledge comes about through the similarity or likeness in the mind of the knower to the thing in the world. Thomas tells us: “This is what the true adds to being, namely, the conformity or equation of thing and intellect.”[47] Josef Pieper points out that all created things are “between two intellects,” the divine intellect, from which they are creatively thought and to which they must conform according to their nature, and the human intellect which comes to know them through its conformity with them. According to St. Thomas the divine intellect “measures” all things, whereas things “measure” our intellect, which can only “measure” things we make (artifacts).[48] Here “measure” relates to the judgment of an intellect, not the “number measure” of the sciences.[49]

Now we have the background to understand why Maritan saw a “nuptial relationship between mind and being.”[50] A key to the relationship is played by what St. Thomas calls the active or agent intellect: “We must therefore assign on the part of the intellect some power to make things actually intelligible, by abstraction of the species from material conditions. And such is the necessity for an active intellect.”[51] Our senses take in input from things in the world, and through the joint work of what St. Thomas calls the common sense and the cogitative and estimative powers of the soul, give rise to a phantasm, or sensible species, all of this being the work of our material bodily organs. But to St. Thomas, the act of the intellect in understanding is not the work of a corporeal organ—understanding is an immaterial act, made possible by the intellective power of the soul. So the corporeal sensible species of the individual concrete thing needs to be, as it were, immaterialized, abstracted, universalized, in order to become an immaterial intelligible species in the intellectual soul. That is where the active intellect comes in. In a subtle and most remarkable act, this agent intellect shines light on the phantasm, like a participated light—to use St. Thomas’ image—enabling the abstraction of immaterial universal intelligible form from material sensible form of the individual sensed thing.[52] Once the intelligible form is in the “possible intellect,” we can form judgments and concepts, and off we go into the process of ratio, or reasoning. To St. Thomas, what we know is not our concepts, but we truly know the thing in the world by means of our concepts, for they turn us back to the thing that is the source of the sensible phantasm.

The key here is that the form of a hylomorphic entity in the world, an existent substance composed of form and matter, comes to be in the intellect of the knower in a manner appropriate to the knower. As Aristotle and Thomas both say, if we see a stone, “the stone is not in the soul, but its likeness is.”[53] A thing has a double existence, as it were, as the thing itself and in the knower as known. We might even think of form having a triple existence: as exemplar in God,[54] in composition with matter in a hylomorphic substance, and as noetic form in the human soul. The world and human beings are so made that the world is intelligible to us. That is the unfathomable mystery of the world’s comprehensibility.

In The Range of Reason, Maritain amplifies on the brief summary given above of Thomistic noetics, by which, in a real and most remarkable sense, all things have the potential to take up residence in the invisible universe of the human mind. In this Conference dedicated to Maritain’s thought, it is worth hearing his own words: “it is precisely the activity of the intellect which extricates from sense experience — and raises to the white heat of immaterial visibility in actu — objects which the senses cannot uncover in things and which the intellect sees: being and its properties, and the essential structures and the intelligible principles seizable in the light of being. That is the mystery of abstractive intuition …”[55] “The process involves an immaterial becoming, an immaterial identification, … To know, therefore, consists of immaterially becoming another, insofar as it is another, aliud in quantum aliud. Thus, from the outset, Thomas Aquinas makes knowledge absolutely dependent upon what is. To know, in fact, is essentially to know something, and something which, as specifier of my act of knowing, is not produced by my knowledge, but on the contrary measures it and governs it, and thus possesses its own being, independent of my knowledge …”[56] “The Thomists have seen that what the intellect thus grasps within itself is not its idea, but the thing itself by means of the idea, the thing stripped of its own existence and conveyed within the intellect, transferred into the intellect’s own immateriality.”[57] “In this act all the vitality comes from the faculty of the subject, all the specification comes from the object, so that the intellection proceeds entirely from the intellect and entirely from the object, because, at the instant when it knows, the intellect is, immaterially, the object itself; the knower in the act of knowing is the known itself in the act of being known …”[58]

Maritain knew that in the sciences we usually do not directly perceive the entities we are studying. Rather, they come to us through scientific instrumentation such as telescopes or microscopes or pointer readings on some instrument and thereby yield a specialized kind of empirical knowledge. Yet, he knew that in the sciences our minds go beyond the deliverances of instruments: “science, in the modern sense of the word — is obliged … to resort to symbols, to entities constructed by the mind, to a sort of mathematical idealization of observed and measured reality, it remains nevertheless that in its deepest dynamism knowledge tends to forms of knowing which, however imperfect they may be, grasp being itself, and which therefore are wisdom as well as science.”[59] Maritain thus points us to end this presentation on the “invisible universe of the human mind” by raising a question. Can the practice of science, which is always done by human beings who have the capacity to see the range of being kath’ holon, be done in a way that brings to science a fuller vision of reality and deeper wisdom than the mere technological ability to control the world?

Towards a better science

This paper has looked at human science according to the order of the true under the aspect of natures, form and formal causes, and their archai, their “beginnings” or grounding principles. But human beings are also desiring beings, as recognized in the opening line to Aristotle’s Metaphysics. Desire speaks of a good, an end, a τέλος, telos, in which it seeks completion. To what end is the insatiable human desire for knowledge directed? We thus come to the order of the good and the notion of the final cause, the “cause of all causes.”[60]

In his Preface to Metaphysics, Maritain makes a key point: “This, then, is what completes the notion of the final cause and renders it clear: the effect itself as foreknown and determining the agent that tends to it.”[61] But this is precisely the point this paper makes above concerning natures, form, and the abstractive capacity of the human mind with respect to the laws of physics: these only make sense in the light of a transcending order of the whole as their grounding principle. It is only by seeing kath’ holon that form and finality, arché and telos, may both be rendered intelligible, and they must be held together in intimate unity if they are held at all. The Principle of Finality holds that every agent acts in view of an end.[62] “Agent” here does not mean only a living or conscious agent. It means anything capable of action. To act or to operate follows upon to be: agere sequitur esse. Existent hylomorphic entities communicate themselves. They act upon other beings. How would we ever know if a being exists if it does not act in some way? In other words, all existent hylomorphic entities enact what they are according to their composite existence as form and matter ordered to some end. This is just as true of atoms or electrons as it is for human beings or stars and galaxies. For example, the end of so simple an entity as a strontium atom is to be a good strontium atom, to enact its nature according to its form and matter. If such an atom turns out to be useful to us as an atomic clock, that is good too, for that is how the unknowing atom fulfills its end as it participates in a wider implicate order of being that includes human agents.

A fundamental philosophical question is that of the one and the many. Aquinas was well aware of several options for understanding the great diversity of beings in the cosmos. Before giving his answer, St. Thomas first mentions an ancient reductive account: “The distinction of things has been ascribed to many causes. For some attributed the distinction to matter … Democritus, for instance, and all the ancient natural philosophers, who admitted no cause but matter, attributed it to matter alone; and in their opinion the distinction of things comes from chance according to the movement of matter.”[63] This sounds very modern: the whole is simply the atoms and the void of Democritus, which, lacking transcendence, leaves the whole ultimately meaningless, grounded in chance and not in goodness. Thus, ultimately, the whole reduces to an unintelligible puzzle with knowledge disconnected from goodness. St. Thomas gives an account that is arguably more intelligible and more attractive: “We must say that the distinction and multitude of things come from the intention of the first agent, who is God. For He brought things into being in order that His goodness might be communicated to creatures, and be represented by them; and because His goodness could not be adequately represented by one creature alone, He produced many and diverse creatures, that what was wanting to one in the representation of the divine goodness might be supplied by another. For goodness, which in God is simple and uniform, in creatures is manifold and divided and hence the whole universe together participates the divine goodness more perfectly and represents it better than any single creature whatever.”[64] A perennial human task is to articulate philosophically how our cosmos, vast in space and time, manifests the goodness of God, given how much more we know now than in the 13th century.

To the Christian mind of Jacques Maritain the rich order of immanent being that we encounter in our universe[65] is grounded in a transcending implicate order of truth, goodness, beauty, and indeed love, if seen kath’ holon according to the divine Logos revealed in Jesus Christ, the Arché and Telos of all things, the beginning and the end, the Alpha and the Omega.[66] And the human being, bearing the image of the Source of all things, gets to put it all into words—words of science, words of mathematics, words of poetry, and words of praise and thanksgiving. To say being in all its depth is a vision worthy of serving. It is why science is both possible and desirable. This coheres with the Patristic and Scholastic theme of exitus/reditus—all things come forth from God and return to him through his human image-bearer who stands in the middle, a microcosm of the macrocosm, on our way to our final end. This paper now ends with Protestant, Orthodox, and Catholic articulations of different but related visions of the human vocation to do good science for the sake of our good God-given end.[67]

Thomas F. Torrance was a 20th-century Scottish Reformed theologian who engaged seriously with the thought of Einstein, Bohr, and Heisenberg. He wrote:[68] “Our scientific knowledge of the universe as it unfolds its secrets to our human inquiries is itself part of the expanding universe. Regarded in this light the pursuit of natural science is one of the ways in which man, the child of God, fulfills his distinctive function in the creation. … Science properly pursued in this way is a religious duty. Man as scientist can be spoken of as the priest of creation, whose office it is to interpret the books of nature written by the finger of God, to unravel the universe in its marvelous patterns and symmetries, and to bring it all into orderly articulation in such a way that it fulfills its proper end as the vast theater of glory in which the Creator is worshipped and hymned and praised by his creatures. Without man, nature is dumb, but it is man’s part to give it word: to be its mouth through which the whole universe gives voice to the glory and majesty of the living God.”

Eastern Orthodox (OCA) priest Alexander Schmemann thought that modern secularism is above all the negation of worship, saying that “the only real fall of man is his noneucharistic life in a noneucharistic world.”[69] Eucharist comes from the Greek word for gratitude or thanksgiving: εὐχᾰριστία, eucharistia. His vision is:[70] “The first, the basic definition of man is that he is the priest. He stands in the center of the world and unifies it in his act of blessing God, of both receiving the world from God and offering it to God—and by filling the world with this eucharist, he transforms his life, the one that he receives from the world, into life in God, into communion with Him. The world was created as the ‘matter,’ the material of one all-embracing eucharist, and man was created as the priest of this cosmic sacrament.”

Canadian Catholic Thomist Charles De Koninck wrote an essay[71] reflecting on the meaning of the evolutionary history of life in our universe. The opening and closing paragraphs are: “Nature realizes its primordial and definitive trajectory in human intelligence. … If God creates, necessarily he creates in order to manifest his glory exteriorly and not to manifest himself to himself, as if, by creating, he could better himself in his own sight. Creation is essentially a communication. Creatures must be able to understand the free gift of this communication, and creation must terminate in an intelligent creature who can glorify its Source. Thus, God could not create a universe that was not essentially ordered to an intelligent creature within that universe.” “In human intelligence the corporeal universe not only becomes present to itself; in addition that presence opens it to all being and thus man can effect an explicitly lived return to the Source of being, God—God who draws the universe to himself in order to be “said” by it and who in this way prepares an abyss where the divinity can live.”

Human science is but one aspect, although a very significant one, of that “saying” to which the human image bearer of the divine Logos in drawn, in the exitus/reditus of all things from and to their Triune Source Who is Being and Love. Creation is a gift, and a human being on a path of theosis[72] through the work of Christ by grace is called to live a life of gratitude and thanksgiving for the privilege of being able to participate in the gift. For this Conference paper, it would be good for Jacques and Raïssa Maritain to have the last word. They remind us in their book Prayer and Intelligence[73] that “Love must proceed from truth, and knowledge must bear fruit in love. Our prayer is not what it ought to be, if either of these conditions is wanting.” May we pray that science may come to see as its highest vocation the seeking of true and fruitful knowledge in the unity of truth and rightly ordered love. That would be to live kath’ holon.

[1] Jacques Maritain, The Range of Reason (Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 1952). The first chapter, from which all quotes come, was first published in THOUGHT: Fordham University Quarterly, Vol. 24, Number 93, June 1949, 225-243.

[2] Servais Pinckaers, O.P., The Sources of Christian Ethics, translated by Sr. Mary Thomas Noble, O.P. (The Catholic University of America Press; 3rd ed., 1995), 242.

[3] Michael Hanby, “Homo Faber and/or Homo Adorans: On the Place of Human Making in a Sacramental Cosmos,” Communio: An International Catholic Review, 38, Summer 2011, 200.

[4] D. C. Schindler, The Catholicity of Reason (Eerdmans, Grand Rapids, MI, 2013), 3.

[5] Andrew Younan, Matter and Mathematics (The Catholic University of America Press, Washington, 2023).

[6] Josef Pieper makes this point in The Silence of St. Thomas: Three Essays (St. Augustine’s Press, 1957), 94-98.

[7] Jacques Maritain, Distinguer pour unir; ou, Les degrés du savoir (Desclée de Brouwer, Paris, 1932).

[8] David Bohm, Wholeness and the Implicate Order (Routledge, 1980). A presentation by Bohm with critiques from various respondents at a 1984 conference at the University of Notre Dame is given in a book edited by D. L. Schindler: Beyond Mechanism: The Universe in Recent Physics and Catholic Thought (University Press of America, 1986); see “Introduction: The problem of mechanism,” by D. L. Schindler (1-12) and “The implicate order: A new approach to the nature of reality,” by David Bohm (13-37).

[9] The English translation of Einstein’s article appears along with his original German in the March 1936 edition of the Journal of the Franklin Institute with the English title “Physics and Reality.” Einstein’s original sentence is, “Das ewig Unbegreifliche an der Welt ist ihre Begreiflichkeit.” The German verb greifen (a root of Begreiflichkeit, “comprehensibility”) means to grab, to grasp, to take hold of.

[10] The Range of Reason, Chapter 1 (THOUGHT, 232).

[11] Wisdom 8:1 and 11:20, NRSV

[12] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, I, Q27, A1, “I answer that … whenever we understand, by the very fact of understanding there proceeds something within us, which is a conception of the object understood, a conception issuing from our intellectual power and proceeding from our knowledge of that object. This conception is signified by the spoken word; and it is called the word of the heart signified by the word of the voice.” In the same response, St. Thomas likens this “procession” in us to the procession of the Persons in the Trinity: “Procession, therefore, is not to be understood from what it is in bodies, either according to local movement or by way of a cause proceeding forth to its exterior effect, as, for instance, like heat from the agent to the thing made hot. Rather it is to be understood by way of an intelligible emanation, for example, of the intelligible word which proceeds from the speaker, yet remains in him. In that sense the Catholic Faith understands procession as existing in God.”

[13] Andrew D. Ludlow, et al., “Systematic Study of the 87Sr Clock Transition in an Optical Lattice”, Physical Review Letters, Vol. 96, 033003 (2006). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.033003

[14] From Prof. M. Endres’ group, California Institute of Technology, https://www.endreslab.com/research.html.

[15] Christian Gross, Immanuel Bloch, “Quantum simulations with ultracold atoms in optical lattices,” Science, Vol. 357, 995-1001(2017). https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.aal3837

[16] A. Einstein, B. Podolsky, and N. Rosen, “Can Quantum-Mechanical Description of Physical Reality Be Considered Complete?”, Physical Review 47, 777-780 (1935). This is Einstein’s most widely cited paper.

[17] The Nobel Prize in Physics 2022 was awarded jointly to Alain Aspect, John F. Clauser and Anton Zeilinger “for experiments with entangled photons, establishing the violation of Bell inequalities and pioneering quantum information science.” From https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2022/summary/

[18] The Nobel Prize in Physics 2001 was awarded jointly to Eric A. Cornell, Wolfgang Ketterle and Carl E. Wieman “for the achievement of Bose-Einstein condensation in dilute gases of alkali atoms, and for early fundamental studies of the properties of the condensates.” From https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2001/summary/

[19] M. R. Andrews et al. “Observation of Interference Between Two Bose Condensates,” Science 275, 637-641(1997). DOI:10.1126/science.275.5300.637

[20] Werner Heisenberg, Physics and Beyond: Encounters and Conversations (Harper and Row, New York, 1971), 41. The words are not verbatim but as later recollected by Heisenberg in describing a walk with Bohr in the mountains near Göttingen, Germany, in the summer of 1922.

[21] In “Kein Chaos, aus dem nicht wieder Ordnung würde,” Die Zeit, No. 34 (22 August 1969), as translated in Physics and Beyond: Encounters and Conversation (1971), 210

[22] Carlo Rovelli, “Physics Needs Philosophy. Philosophy Needs Physics,” Foundations of Physics 48, 481–491 (2018).

[23] D. C. Schindler, “Truth and the Christian Imagination: The Reformation of Causality and the Iconoclasm of the Spirit,” Communio 33 (Winter, 2006).

[24] Brill Dictionary of Ancient Greek (BDAG), ed. By F. Montanari et al. (Brill, Len, 2015); theoria also bears the sense of contemplation, or receptive beholding, thus playing an important role in the Christian tradition.

[25] Aristotle, Metaphysics A 980a 21, πάντες ἄνθρωποι τοῦ εἰδέναι ὀρέγονται φύσει. The verb ὀρέγονται in the middle voice means to stretch oneself out, to extend oneself, or to grasp. It correlates with human desire, appetite, ad petere, striving for. The infinitive εἰδέναι comes from the very rich and polyvalent verb εἴδω, which bears the sense to see, perceive, look at, regard, but also to know, understand, and, poetically, to appear, be visible, and even to become like or similar (Greek meanings are from BDAG). Sachs, in his Aristotle’s Physics (Rutgers University Press, 1995) Book 2, Chapter 1, 193a 30, characterizes εἶδος, form, as “the look that is disclosed in speech,” translating Aristotle’s full sentence as: “In one way then, nature is spoken of thus, as the first material underlying each of the things that have in themselves a source of motion and change, but in another way as the form, or the look that is disclosed in speech.” The form is the “invisible” principle or meaning of a thing that by virtue of a thing being seen by the eyes is capable of being grasped by the mind and thus articulated in human speech. This coheres with St. Thomas’s understanding of human perception by which form in the world, reflecting the exemplar causation of the Creator, comes to be form in the intellect of the human perceiver that can then proceed in speech as an intelligible word.

[26] J. Sachs, Aristotle’s Metaphysics (Green Lion Press, 1999), Glossary; see also previous footnote.

[27] “Hylomorphic” is derived from the Greek words for matter, ῡ̔́λη, and form, μορφή. The latter is a second word that Aristotle uses for form, which J. Sachs says in his Glossary to Aristotle’s Metaphysics indicates shapeliness, implying an active shaping.

[28] J. Maritain, A Preface to Metaphysics: Seven Lectures on Being, (Sheed and Ward, London, 1943), Lecture 3, 10: “What do I mean by the phrase eidetic visualisation, abstractio? I mean that the intellect by the very fact that it is spiritual proportions its objects to itself, by elevating them within itself to diverse degrees, increasingly pure, of spirituality and immateriality. It is within itself that it attains reality, stripped of its real existence outside the mind and disclosing, uttering in the mind a content, an interior, an intelligible sound or voice, which can possess only in the mind the conditions of its existence one and universal, an existence of intelligibility in act.”

[29] “Noetics,” referring to how our minds come to understand the world, derives from the Greek word for “thinking, νόησις, noesis.”

[30] J. Sachs, Aristotle’s Physics, Book 1, Chapter 1, 184a: “Since, in all pursuits in which there are sources or causes or elements, it is by way of our acquaintance with these that knowing and understanding come to us (for we regard ourselves as knowing each thing whenever we are acquainted with its first causes and first beginnings, even down to its elements), it is clear that also for the knowledge of nature one must first try to mark out what pertains to its sources.” Ἐπειδὴ τὸ εἰδέναι καὶ τὸ ἐπίστασθαι συμβαίνει περὶ πάσας τὰς μεθόδους, ὧν εἰσὶν ἀρχαὶ ἢ αἴτια ἢ στοιχεῖα, ἐκ τοῦ ταῦτα γνωρίζειν (τότε γὰρ οἰόμεθα γιγνώσκειν ἕκαστον, ὅταν τὰ αἴτια γνωρίσωμεν τὰ πρῶτα καὶ τὰς ἀρχὰς τὰς πρώτας καὶ μέχρι τῶν στοιχείων), δῆλον ὅτι καὶ τῆς περὶ φύσεως ἐπιστήμης πειρατέον διορίσασθαι πρῶτον τὰ περὶ τὰς ἀρχάς.

[31] BDAG

[32] J. Sachs, Aristotle’s Metaphysics (Green Lion Press, 1999), Book IV, Chapter 2 1003a21. “Being is meant in more than one way, but pointing towards one meaning and some one nature rather than ambiguously.” (τὸ δὲ ὂν λέγεται μὲν πολλαχῶς, ἀλλὰ πρὸς ἓν καὶ μίαν τινὰ φύσιν καὶ οὐχ ὁμωνύμως). See J. Maritain in Preface to Metaphysics, Lecture 4: “Being presents me with an infinite intelligible variety which is the diversification of something which I can nevertheless call by one and the same name.”

[33] ἐν ἑαυτοῖς ἀρχὴν κινήσεως καὶ στάσεως, Aristotle, Physics, Book II, Chapter 1, 192b22; J. Sachs translates this section to say that a thing that is by nature “has in itself a source of motion and rest, either in place, or by growth and shrinkage, or by alteration.”

[34] Thomas Aquinas, Commentary on Aristotle’s Physics, Book II, Lecture 1, 145. J. Sachs translates it as “nature is a certain source and cause of being moved and of coming to rest in that to which it belongs primarily, in virtue of itself and not incidentally.”

[35] This issue is discussed at length in several parts of Matter and Mathematics.

[36] Roland Omnes, Quantum Philosophy: Understanding and Interpreting Contemporary Science (Princeton University Press, 1999).

[37] This is not negated by the fact that all atoms (or “particles”) of a certain kind are absolutely identical, leading to the specific properties of ensembles of bosons (particles with integer spin) or fermions (particles with half an odd integer spin). It is always possible, for example, to distinguish through measurement “this atom” from “that atom,” for measurement actualizes distinct potencies of the whole.

[38] Josef Pieper, The Silence of St. Thomas: Three Essays (St. Augustine’s Press, 1957), 46.

[39] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, I.Q3.A4: “I answer that, God is not only His own essence, as shown in the preceding article, but also His own existence. This may be shown in several ways.”

[40] Ibid., I.Q44.A1: “Therefore all beings apart from God are not their own being, but are beings by participation. Therefore it must be that all things which are diversified by the diverse participation of being, so as to be more or less perfect, are caused by one First Being, Who possesses being most perfectly.”

[41] See, for example, Cornelio Fabro, Selected Works, Volume 1, Selected Articles on Metaphysics and Participation (IVE Press, 2016); W. Norris Clarke, S. J., Explorations in Metaphysics: Being, God, Person (University of Notre Dame Press, 1994), Chapter 5, “The Meaning of Participation in St. Thomas;” David C. Schindler, “What’s the Difference? On the Metaphysics of Participation in a Christian Context,” The St. Anslem Journal 3.1 (Fall, 2005).

[42] The philosophical concept of participation is associated with the Greek noun μέθεξις, methexis, and the related verb μετέχω, compounded from the preposition μετά, meta, and the verb ἔχω, echo, “to have” or “to possess.”

[43] Summa Theologica I.Q13.A5, in which St. Thomas also quotes Romans 1:20: “The invisible things of God are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made.” To St. Thomas human knowing comes from taking in sensory impressions from the created things of the world, but God is invisible, uncreated and unboundedly exceeds all created things. Consequently, our language based on things that we can see and hear and touch or experience in the world (“creatures”) can only bear rightly on God and convey real truth when used in an analogical sense.

[44] See “The Fourth Lateran Council’s Defintion of Trinitarian Orthodoxy,” by Fiona Robb, Journal of Ecclesiastical History (Cambridge University Press), Vol. 48, Issue 1 (1997) 22-43. The Latin in Canon 2 is “inter creatorem et creaturam non potest tanta similitudo notari, quin inter eos maior sit dissimilitude notanda.” See also H. Denzinger, The Sources of Catholic Dogma (Loreto Publications, 2002) 432.

[45] Silence of St. Thomas, 68: Pieper says “the ‘negative element’ in the philosophy of St. Thomas, which we set out to formulate, must be envisaged against the background of an embracing affirmation. That the essences of things are unknowable is part of the notion of the truth of Being. But so little does this denote objective inaccessibility, the impossibility of cognition, or darkness on the part of things, that there is, on the contrary, this striking paradox: In the last resort, things are inaccessible to human knowledge precisely because they are all too knowable.”

[46] In De Veritate 1.1 St. Thomas gives his understanding of the true and the good “based on the correspondence (convenientiam) one being has with another. This is possible only if there is something which is such that it agrees with (convenire) every being. Such a being is the soul (anima), which, as is said in The Soul, ‘in some way is all things (quae quodammodo est omnia).’ The soul, however, has both knowing and appetitive powers. Good expresses the correspondence (convenientiam) of being (entis) to the appetitive power, for, and so we note in the Ethics, the good is ‘that which all desire.’ True expresses the correspondence (convenientiam) of being (entis) to the knowing power, for all knowing is produced by an assimilation (assimilationem) of the knower to the thing (res) known, so that assimilation is said to be the cause of knowledge.” It is precisely in the “agreement” (convenientiam), or “similarity, likeness” (assimilationem), between the mind or soul and a thing (res) that accounts for what it means for something to be “true.”

[47] Thomas Aquinas, De Veritate 1.1.

[48] Pieper, Silence of St. Thomas, 54; see De Veritate 1.2.

[49] In Summa Theologica I.Q79.A9, St. Thomas says “… to ‘judge’ or ‘measure’ (mensurare) is an act of the intellect, applying certain principles to examine propositions. From this is taken the word ‘mens’ (mind).”

[50] Quoted by W. Norris Clarke, The One and the Many: A Contemporary Thomistic Metaphysics (University of Notre Dame Press, 2001), Chapter 1, Section V.

[51] Summa Theologica, I.Q79.A3.

[52] Ibid., I, Q76, 4, “we must say that in the soul is some power derived from a higher intellect, whereby it is able to light up the phantasms. … the power which is the principle of this action must be something in the soul. For this reason Aristotle (De Anima iii, 5) compared the active intellect to light, which is something received into the air: while Plato compared the separate intellect impressing the soul to the sun, as Themistius says in his commentary on De Anima iii. But the separate intellect, according to the teaching of our faith, is God Himself, Who is the soul’s Creator, and only beatitude; as will be shown later on (Q90.A3).”

[53] Ibid., I.Q76.A4, “what is understood is in the intellect, not according to its own nature, but according to its likeness; for ‘the stone is not in the soul, but its likeness is,’ as is said, De Anima iii, 8. Yet it is the stone which is understood, not the likeness of the stone; except by a reflection of the intellect on itself: otherwise, the objects of sciences would not be things, but only intelligible species.”

[54] Ibid., I.Q44.A3, “I answer that, God is the first exemplar cause of all things … divine wisdom devised the order of the universe, which order consists in the variety of things. And therefore we must say that in the divine wisdom are the types of all things, which types we have called ideas—i.e. exemplar forms existing in the divine mind.”

[55] The Range of Reason (THOUGHT, 232).

[56] Ibid, 236.

[57] Ibid, 239.

[58] Ibid., 238.

[59] Ibid., 240.

[60] Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica (ST), I, Q5, A2, Reply Obj. 1: “goodness, since it has the aspect of desirable, implies the idea of a final cause, the causality of which is first among causes, since an agent does not act except for some end; and by an agent matter is moved to its form. Hence the end is called the cause of causes.”

[61] Preface to Metaphysics, p. 119

[62] Ibid., p. 105; see additional details in Lectures 5 and 6, pp. 90-152.

[63] ST I, Q 47, A1.

[64] Ibid.

[65] The word “universe” is derived from Latin roots that mean to be turned towards one, unity.

[66] The Revelation of St. John, 1:8, 21:6; in 22:13, one of the closing verses to the last chapter of the Bible, Jesus says: “I am the Alpha and the Omega, the first and the last, the beginning and the end,” ἐγὼ τὸ ἄλφα καὶ τὸ ὦ, ὁ πρῶτος καὶ ὁ ἔσχατος, ἡ ἀρχὴ καὶ τὸ τέλος.

[67] A handout with these three quotations was handed out to the audience of the original talk.

[68] T. F. Torrance, The Ground and Grammar of Theology (T&T Clark, 2005), pp. 15-16

[69] Alexander Schmemann, For the Life of the World: Sacraments and Orthodoxy (St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2000); see Chapter 1, Part 4, and Appendix 1, “Worship in a Secular Age.”

[70] Ibid., Chapter 1, Part 2.

[71] Charles De Koninck, “The Universe: Desire for Thought,” translated by J. M. Hubbard, Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture, Volume 17 (Winter 2014) 172-184. The original is “Le Cosmos comme Tendence vers la Pensée,” Itinéraires 66 (1962) 168–88.

[72] Theosis, θέωσις, is of the essence of Christian salvation in Christ as understood in Eastern Orthodox Christianity, and it plays a significant role in Western Roman Catholicism as well. The concept dates to the ancient Church Fathers, as early as St. Athanasius (296-373 CE), On the Incarnation of Christ. It refers to the Scriptural notion of the union and progress of a redeemed human person with God through the work of Christ and the Holy Spirit in one who is seeking to be ever more conformed to the image of God in Christ as an adopted son or daughter of God through grace, on the way to one’s ultimate final destiny given by God. Many Protestants appreciate the concept of transformation in Christ, even if they articulate it differently from the Orthodox or Catholics.

[73] Jacques and Raïssa Maritain, Prayer and Intelligence & Selected Essays, translated by A. Thorold, J.W. Evans, and J. Kernan (Cluny, Providence, 2016), p. 1.