This essay was written before a trip to Beijing in April 2016 to speak at a physics conference and give five lectures on physics to Chinese students at Tsinghua University. It was revised after returning, and revised again in May 2019. … Paul S. Julienne

Prolegomena

This essay was started prior to a trip to China in 2016 and was completed after returning. I was traveling to speak at a physics conference and to present some tutorial lectures at Tsinghua University in Beijing on the physics of very cold atoms. It is worthwhile to consider why the title refers both to Christ and to the Chinese term dao. These two might have more in common than apparent at first sight, if only because the Chinese word dao (道) is used to render the Greek word logos (λόγος) in the opening verse of the Chinese translation of St. John’s Gospel.[1] While this Greek term is rendered as “Word” and identified with Christ, John the Theologian undoubtedly had in mind its other use as a philosophical term pointing to the fundamental “order” or “rationality” or “logic” of the whole cosmos. Both science and theology aim at comprehending the fundamental order of the world.

In his book, The Abolition of Man, C. S. Lewis also used the Chinese term dao (using the older spelling, tao) as an organizing principle behind his essential point. Most of humanity has lived within the dao for most of human history. All of the religions of the world, including Christianity, have known this, as Lewis illustrates by quotations from dozens of different religions in the book’s Appendix. To live within the dao is to live in such a way that human beings must answer to a given and transcendent order outside of themselves, beyond their control, where they are not master. It is modern humanity with its totalizing mastery of the world through technology that insists on living outside the dao. Postmodern humanity is on the verge of doing that. To live outside the dao is to forget and thus to abolish our humanity. So let us pay attention, if we have eyes to see and ears to hear, lest we become unwitting perpetrators in the destruction of our civilization.

On to Beijing

At the start of a church conference, I was sitting around the table having breakfast with some of the participants. I mentioned my upcoming trip to China to speak at a physics conference. My friend Clint from my church asked me a simple question from physics about something that he did not understand. This sparked a remarkable train of thought that strikes at the heart of Reality and how we understand it, not unrelated to the “nuptial theology” and peacemaking with which my church has been involved for some time now. It is hard to know where to begin.

Clint’s simple question is why is a neutron stable in a nucleus, but dies quickly when alone? A neutron is a fundamental “particle” that is known to be unstable when in free space as an isolated particle, where neutrons freed from atomic nuclei have a lifetime of around 15 minutes. We also know that stable atomic nuclei are comprised of protons and neutrons, and many nuclei “live forever” as a combination of protons and neutrons—that is they are stable.

The answer in many ways is simple, but it takes us into the heart of quantum physics and fundamental concepts in physics. Perhaps the deepest answer is that of “broken symmetry,” that is to say, there are fundamental “symmetries” in the world that give the world its richness in the very act of their being broken. Examples abound, for example, in Big Bang cosmology (broken symmetry being essential for the world being as it is) or “time’s arrow” and entropy, as well as many much more mundane physics problems.

Let us take the simplest example: heavy hydrogen, or the deuteron, a simple combination of a neutron and a proton. The deuteron is known to be stable (although barely so), because it is a combination of two particles. One alone is not stable; two together are. This is because of broken symmetry. The neutron in free space, isolated and alone, has a short lifetime, a few minutes, because the combination of quarks that make the neutron can not live in the symmetry of isolation—space infinitely extended in all directions. The quantum state of being alone in an infinite vacuum is too “symmetric” as it were, and the neutron exists in a state that can only fall apart. On the other hand, when the neutron is in combination with a proton, a different fundamental particle to which it is attracted, it becomes stable, it acquires a new identity as a deuteron in which the proton, as it were, “gives life” to the neutron by breaking the symmetry of its perfect isolation in a vacuum (which is anything but a vacuum, but that is another matter). The neutron and the proton, by virtue of their being together, hold one another in an indissoluble bond of stability. Fertile ground for more thought development here.

So I was able to explain to Clint something about the quantum physics of the neutron, that lets it become stable when it is in combination with another. This is an interesting, and fascinating “nuptial analogy” or “resonance” in the natural world. Much can be done with that wonderful term “resonance,” for I have written many physics articles about “resonances,” which are precisely the topic of my talks in China, where I am teaching about “resonances” in certain kinds of physical phenomena.

Well there is a lot of interesting physics here, no doubt. But what does it have to do with going to China? Well, a lot, actually. I have been doing some background study and reading in my preparation, and decided to look into some Chinese history and patterns of thinking about the world, so as to better understand my hosts and their country. This led to a PowerPoint slide I made as a lead-in to the physics conference at which I will speak. My idea was to draw upon the ancient traditions of China to make an important point about physics and to introduce essential concepts for my and my colleagues’ talks.

But first, let me consider a bit of Chinese history. Two of the great “masters” or sages of ancient China, from the 6th century BCE were Confucius and Laozi,[2] who lived before either Plato or Aristotle. Both wrote short works, quite different in import, that have been extraordinarily influential, not only in China but in the world beyond. Laozi gave us the Daodejing, concerning the Way, or Dao, that has guided much of Chinese life ever since. The era after them from 475-221 BC was known as the “Warring States Period,” which one of my course books described as a period of “political turmoil, social breakdown, and tremendous suffering.” The thinking of Confucius and Laozi, who gave quite different answers on how one should live in such a time, continued to be developed in this era, which generated the “Hundred Schools” of Chinese thought. One should not think that there is but one interpretation of dao, but many.

“Dao” may be translated as “way” or “path”. But that cannot possibly do it justice. The Dao is fundamentally unspeakable: to say what it is is already to say too much. Yet one cannot fail to speak of it. It is captured in part by a well-known symbol, that of the intertwining “yin” and “yang,” the opposites from which the world and our understanding of it derive (according to the ancient Chinese). This makes a nice introduction to some quite interesting physics and led me to create this introductory slide to my talk, which concerns how we interweave scientific concepts of great complexity and great simplicity to bring order into our understanding of some very complex phenomena we are seeking to understand. There is a “way or “path” that lets us get to understanding. So my “science” slide uses the yin-yang symbol and the Chinese character for “Dao” from an ancient bronze artifact to make the point.

What does the Dao have to do with Christ? The Dao is a way or a path. Yet Jesus called himself the way, the truth, and the life. The question is an echo from the East of a similar question that Tertullian of Carthage asked from the West: what does Athens have to do with Jerusalem? [3] Some say they could not have anything to do with one another. But to say this is perhaps to know neither the Dao nor the Christ.

The early “Church Fathers” like Justin Martyr, Clement of Alexandria, and later, Augustine of Hippo agreed on one thing, quite contrary to Tertullian’s negative answer about Athens and Jerusalem. These “Fathers” articulated a more mainstream view among the early Christians that pagan learning often captured truth that now can come to its fulfillment in Christ.[4] That is, we should learn from it and use it.

Could the Dao be a preparation for Christ, such that the Chinese have within their ancient traditions the resources that can help them understand and embrace the good news of the cross of Christ? The yin and yang certainly have an affinity with the mystagogical tradition of the Christian East, the kataphatic/apophatic distinction of the Greek “Fathers,” the Chalcedonian statement of the union of the human and divine in Christ, and the via positiva/via negativa of the West.

But there are absolutely essential differences between the Dao and Christ that are essential to maintain and that have the power to transform this ancient Chinese tradition by introducing a new element. The element is precisely broken symmetry, which alone gives life. There is so much to be said here, such a richness of depth that I can only touch on it briefly now.

The yin and the yang speak of opposites: light and shadow (their literal meanings point to the south and north sides of a mountain), masculine and feminine, hot and cold, dry and wet, etc.–all aspects of the way we experience in the world. The problem, as I see it, with the yin and yang is that in the Dao they are too symmetric, both holding an equal power. The yin-yang symbol has perfect symmetry and consequently fails to capture an essential asymmetry in the world. Thus, good and evil are ultimately reconciled as being two intertwined, essential, and unbreakable elements of the world we live in: one can be passive in the world, accepting its evil as inevitable to go along with its good.[5] On the other hand, the Hebrew Scriptures together with the good news of Jesus “break the symmetry” and “give life,” in a Trinitarian and Incarnational dynamic (perichoresis) of self-giving love, a kenotic (Phil 2:7) source of all our rescue from the power of evil in the world. Christ unmasks and overcomes the evil in the world, and its powerful hold over us individually and collectively.

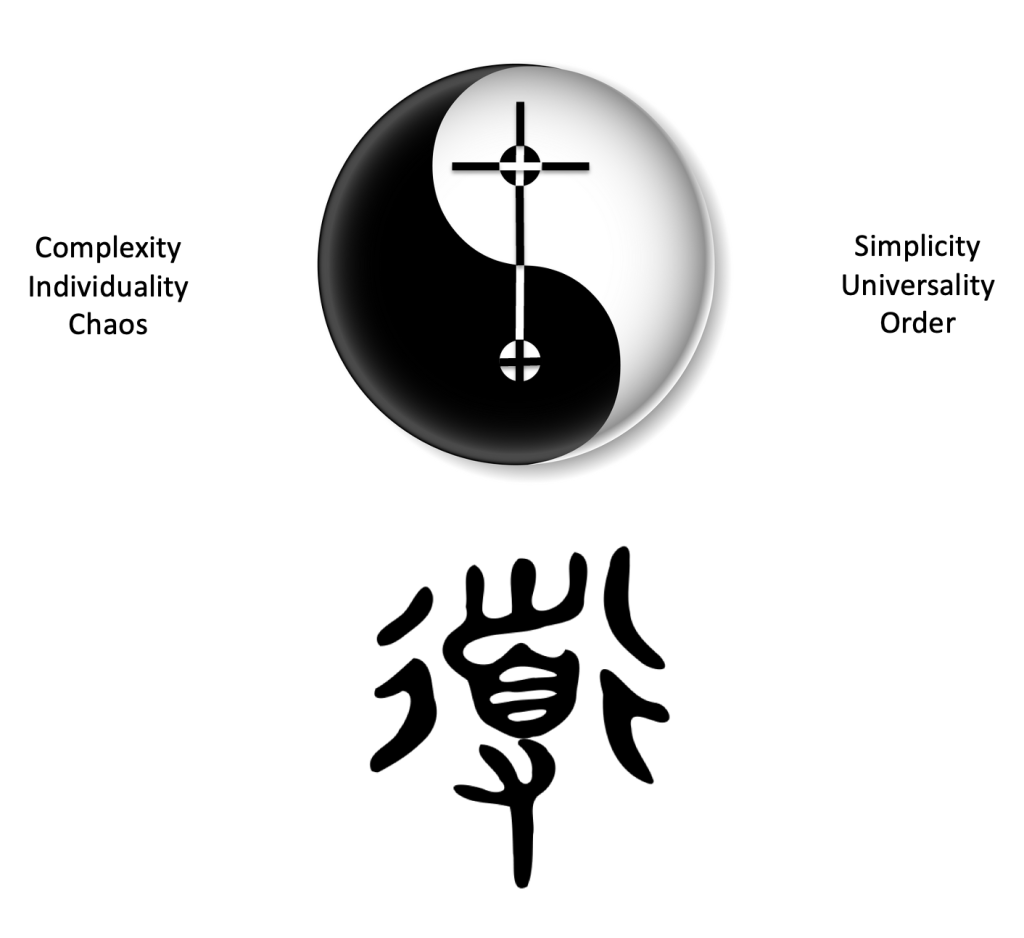

All things are ultimately simple and cohere in the love of God in Christ Jesus, the creative principle—Word, Logos—of the world.[6] There is a simple transformation of the Dao that breaks its symmetry and thereby gives to this ancient symbol the power of life. Namely (for how we name things is so crucial[7]), the Cross of Christ :

When the Cross is added to the yin-yang as a new element, rooted in the depths of darkness with roots in light and life, it ascends from the darkness into the light, where in the transformed[8] picture the outstretched arms of Christ on the Cross cut through the darkness—literally crossing it out—and breaks the symmetry. This “broken symmetry”—given by pure love broken for our sake–transforms the yin-yang symbol into a sign of the Way, the Truth, and the Life that the good Creator offers to create in us through the work of his Son and his Spirit, the Giver of Life. As Sir John Polkinghorne likes to put it,[9] his best candidate for a “theory of everything”[10] is Trinitarian theology.

Therefore, could it be that the good Father, in his good Providence, has through the work of his Spirit prepared the Chinese—and all who know the unspoken depth of the Dao—to receive the good news of the gospel, the only truly good news in the world. Christ fills the Dao with new meaning by breaking its symmetry, showing the actuality of goodness and the emptiness of evil. Could it be that the Dao has been a schoolmaster to prepare the Chinese for Christ, just as Clement of Alexandria taught that their philosophy was a schoolmaster to prepare the Greeks for Christ?

This is a path worth walking, to explore the depths of its richness. It is a path towards peace, a peace that passes understanding.

After returning

Interestingly, I discovered after my lectures that the ancient Chinese character from a 2nd-century bronze inscription of dao that I used on my “science” slide was not readable by my contemporary Chinese audience—they had to ask what it was, but immediately understood when I mentioned “dao.” I did not show the symbol with the cross, but this is something to be developed.

Having read the quite short “Daodejing” on the flight over, I have more of an appreciation of the ancient Chinese way of thinking about the Dao. There is a long history in Chinese history up to this day reflecting on the various meanings of language and human words, the “dao” of “nature” or “tian” (“heaven,” the “sky” or “cosmos”), and the social “daos” of human invention and culture. The “Daoist” reading has been developed in conjunction with the reading of Confucius, and the “hundred schools” that developed during the “warring states” era (475-221BC), especially the schools of Mozi, Huizi, and his friend, Zuangzi. The latter developed the thinking of the “Daoist” strand. Much of this has been picked up and reflected upon by Asian and Western thinkers in modern times. The Chinese path has both connections and significant differences with the Western philosophical tradition.[11]

There is much thought to be developed here: knowing how the world works does not give us what we “ought” to do, that is, as all the great scientists know, science does not give us ethics. Yet we all must have a basis for the choices we have to make in the world. Is our way of living to be based on tradition and practice (Confucius, Mencius), or utility (Mozi), or a “natural” or “social” dao (Laozi, Zuangzi). The path walked by Zuangzi is a skeptical path marked by both subtlety and epistemic humility.

The path given to us by Christ is also one of humility. The fundamental question addressed to us by Christ is the same as the one encountered by the ancient Chinese. Are we to base our lives on something that is given to us as an absolute in conformity with the nature of the reality of the world (in Christianity, Christ reveals to us “the way, the truth, and the life:” the way to the Father, the truth of the Logos, the Spirit as the “giver of life”). In ancient Chinese thinking, the “way” is given by “tian” or “heaven,” that is, a given order of things, the known-but-unknown Dao. Or are our lives only to be governed by human constructs (the “social daos”) of our own making? It all sounds very postmodern. Do we conform to “nature” as given or do we lift ourselves by our own bootstraps in this puzzling and unknowable world in which we find ourselves? Similar questions are posed by the philosophies and religions of India.

Ultimately, we have to make judgments, that is, order our lives according to some perceived ends, but on what basis do we come to make them? It is a matter of discernment, but we cannot extricate ourselves from the path that has formed us. Christ is unique—the Logos that breaks the symmetry of the problem of language and gives us a unique path to the Father. Do our words actually name anything that is not of our own making? The ancient Chinese knew the problem quite well. The ancient Hebrews well knew the significance of a Name, as did Aquinas: God gave his two names to Moses (Exodus 3:14-15), expressing comprehensible concreteness (“the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob”) and unfathomable mystery (The unpronounceable and holy “I am who I am”). In that most human of things, symbolic language, do we name something real though veiled? Or do we name the inventions of our own minds? Perhaps on this question—what do we name when we use language–hinges the future of humanity and the world.

Can we be guided by ancient thinkers:

- As the Preacher says, there is nothing new under the sun (Eccl. 1:9):

- Is the world one (Parmenides)? Is the world many (Heraclitus)?

- Is it number (Pythagoras)?

- Is it only atoms and the void (Democritus)?

- Is it form (Plato) or substance (Aristotle)?

- Is the multiplicity of the world a gift of three who are one (Genesis 1:1-3, where God’s speech and God’s spirit are active with God in bringing the world to be)?

- What is the “reason” behind all things? Is it the Logos (John 1:1)?

- Is there a way, a path (a dao) to understanding (Psalm 119:105; John 14:6)?

Is the world simple? Is it complex? Is it complex in its simplicity, simple in its complexity? Coming full circle, from the neutron that is given stability in its relation with a proton, I was led to this poem:

The wonder that we count[12]

One neutron.

It dies.

Add one proton. Make one out of two.

It lives.

Take two of the ones that live and make one again.

Alpha, the beginning.

Take three of the ones that are four and make Carbon.

Carbon makes us.

We live because of simple numbers.

Is number real?

Are our words numbered?

How can we speak them?

Is it because of the One who is three in being one?

Does that tell us of Omega, the end?

This world is no accident. All we know about it conforms to its Logos: word, simplicity, intelligibility, fire, desire, love. The Dao of the ancient far-east needs to be completed by the cruciform shape of Love.

Postscript

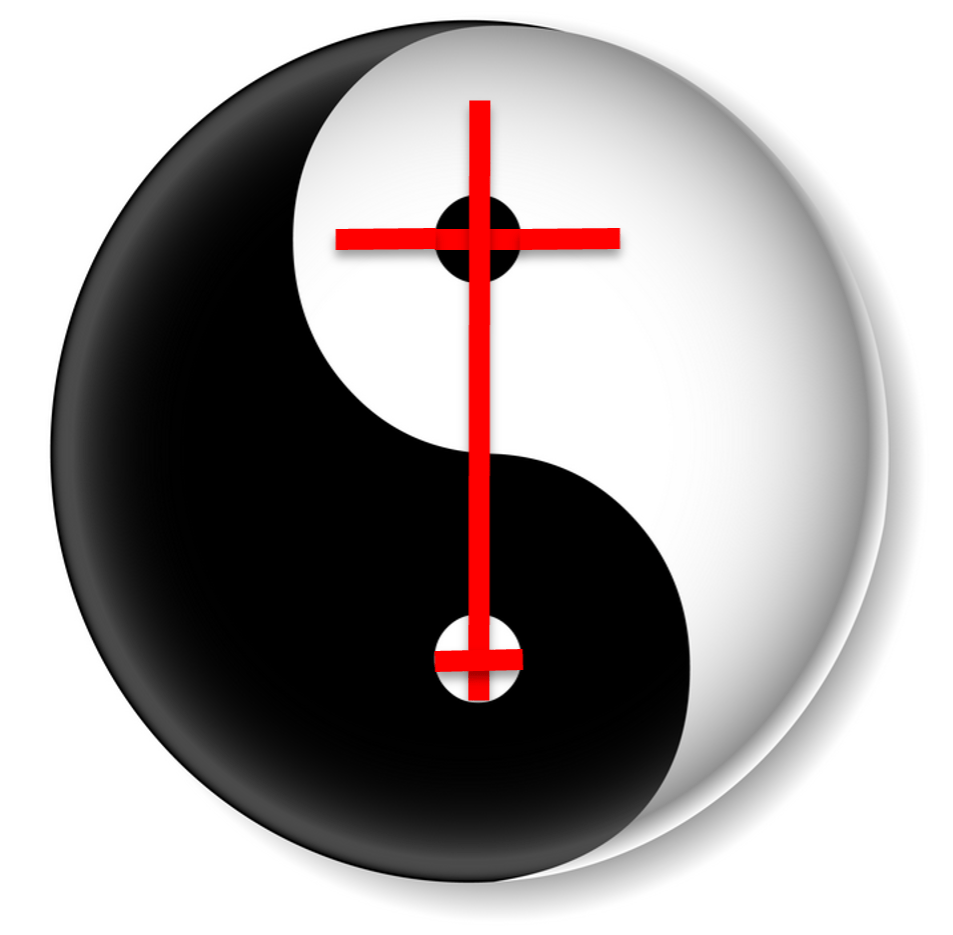

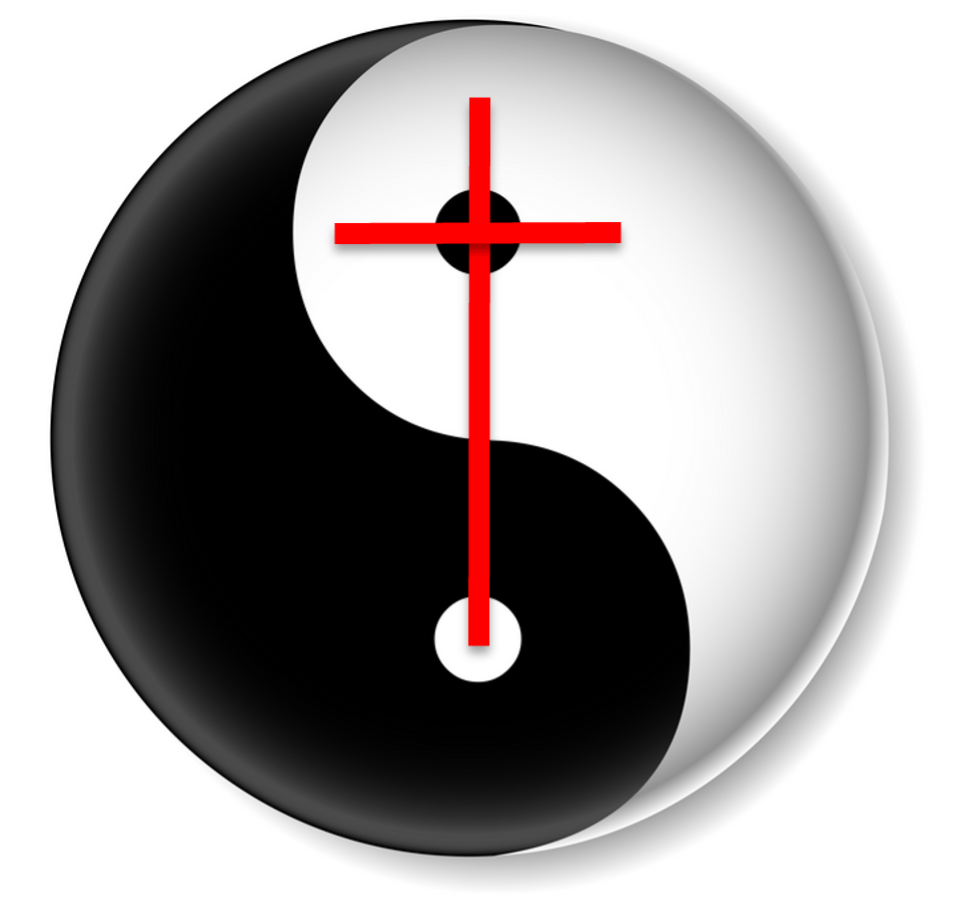

Reflecting on the “crossed-yin-yang” symbol, I have tried a couple variations. Red is the color of good fortune and joy in Chinese culture. Thus, to color the cross red is a natural thing to add. Heb. 12.2: “Jesus, the founder and perfecter of our faith, who for the joy that was set before him endured the cross.” The color red also picks up on the blood of Christ, a powerful Christian symbol of new life and rescue.

There are two ways I have thought of this:

The upper way keeps the “cross” symmetry at the bottom and top, with the top “breaking the symmetry” by the cross being extended into the light in 3 directions. The upper version has the cross with “roots” in the light at the bottom, which the darkness has not extinguished. The lower version lacks the “roots” and uses a more conventional cross symbol, now superimposed on the yin-yang symbol. The upper version seems more “natural” to me to the symmetry of the yin-yang, with the broken symmetry of the roots not extending into the darkness at the bottom, but the extended arms of the cross extending into the light at the top.

Endnotes

[1] John 1:1, 太初,道已经存在,道与上帝同在,道就是上帝. Tàichū, dào yǐjīng cúnzài, dào yǔ shàngdì tóng zài, dào jiùshì shàngdì. Google translate: “In the beginning, the Word was already there, the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” In his new translation of the Greek New Testament, David Bentley Hart says “One standard Chinese version of the Bible renders logos in the Prologue of John’s gospel as dao, which is about as near as any translation could come to capturing the scope and depth of the world’s religious, philosophical and metaphoric associations in those verses, while also carrying the additional meaning of ‘speech’ or ‘discourse.’”

[2] It is believed that neither Kongzi ((“Master Kong,” 551-479 BCE) or Laozi (literally, “venerable master” or “old master,” around 600-530 BCE) wrote a book of their own. The latter may be a more legendary than historical figure. In any case, their followers collected sayings associated with them and eventually put them into writing.

[3] In Tertullian’s On the Rule of the Heretics, written in Latin in the early 3rd century: “For philosophy provides the material of worldly wisdom, in boldly asserting itself to be the interpreter of the divine nature and dispensation. The heresies themselves receive their weapons from philosophy … It is the same subjects which preoccupy both the heretics and the philosophers. Where does evil come from, and why? Where does human nature come from, and how? … What is there in common between Athens and Jerusalem? Between the Academy and the church? Our system of beliefs comes from the Porch of Solomon, who himself taught that it was necessary to seek God in the simplicity of the heart. So much the worse for those who talk of a “stoic”, “platonic”, or “dialectic” Christianity. We have no need of curiosity after Jesus Christ, nor for inquiry after the gospel.” Tertullian’s negative view regarding philosophy was NOT to become the majority view of the Christian tradition; see footnote 4.

[4] Clement of Alexandria in Stomata, written in Greek in the early 3rd century, wrote: “Thus until the coming of the Lord, philosophy was necessary to the Greeks for righteousness. And now it assists those who come to the faith by a way of demonstration, as a kind of preparatory training for true religion. For “you will not stumble” (Proverbs 3:23) if you attribute all good things to providence, whether it belongs to the Greeks or to us. For God is the source of all good things, some directly (as with the Old and the New Testaments), and some indirectly (as with philosophy). But it might be that philosophy was given to the Greeks immediately and directly, until such time as the Lord should also call the Greeks. For philosophy acted as a schoolmaster to bring Greeks to Christ, just as the law brought the Hebrews. Thus philosophy was by way of a preparation, which prepared the way for its perfection in Christ.”

Augustine of Hippo in On Christian Doctrine, written in Latin around 397 AD, said: “If those who are called philosophers, particularly the Platonists, have said anything which is true and consistent with our faith, we must not reject it, but claim it for our own use, … pagan learning is not entirely made up of false teachings and superstitions … It contains also some excellent teachings, well suited to be used by truth, and excellent moral values. Indeed some truths are even found among them which relate to the worship of the one God. Now these are, so to speak, their gold and their silver, which they did not invent themselves, but which they dug out of the mines of the providence of God, which are scattered throughout the world, yet which are improperly and unlawfully prostituted to the worship of demons. The Christian, therefore, can separate these truths from their unfortunate associations, take them away, and put them to their proper use for the proclamation of the gospel.”

[5] This comes out in the Chinese notion of wu wei, an attitude of passive non-action in human affairs, that developed in early Daoism and Confucianism, that bears similarity to the Stoicism that developed in the Greco-Roman world; see J. Yu, “Living with nature: Daoism and Stoicism,” History of Philosophy Quarterly, Vol. 25, No. 1 (Jan., 2008), pp. 1-19. Both Daoism and Stoicism emphasize being in harmony with “nature,” φύσις (Greek) or ziran (Chinese); or to put it in popular language, “to go with the flow.”

[6] For my 2014 essay for BioLogos, “Word and Fire,” on science and the Logos.

[7] My 2015 essay for BioLogos reflects on the analogical use of language from a Christological perspective.

[8] Μετανοεῖτε (Matt. 4:17); μεταμορφοῦσθ (Rom. 12:2)

[9] In Science and The Trinity. Polkinghorne is an Anglican priest, formerly president of Queen’s College, Cambridge, and a mathematical physicist who trained under Nobel laureate Murray Gell-Mann.

[10] The “unified field theory” of physics that Einstein unsuccessfully worked so hard to get.

[11] For example, commentary on Zuangzi and his significance in Western thinking is available at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/zhuangzi/, which has a “postmodern” ring to it.

[12] Notes on the poem: an isolated single neutron is stable for around 15 minutes before decaying; a neutron and a proton combine to make a stable deuteron (made from 2 particles); two deuterons make an alpha particle (made from 4 particles); three alpha particles make a carbon nucleus (necessary for life, along with the heavier elements). See this link for my article on carbon formation in the universe.